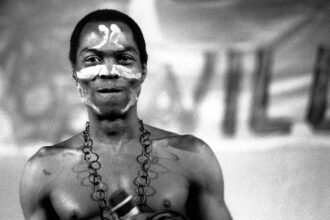

Grammy-nominated Afrobeat legend Femi Kuti has described the posthumous Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award conferred on his late father, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, as long-overdue global recognition of a life devoted to confronting dictatorship, corruption and social injustice in Nigeria and across Africa.

Speaking during an interview with ARISE News on Friday, Femi said the honour carries profound emotional, cultural and historical significance, especially for those who lived through the repressive military era that shaped Fela’s music and activism.

“Everybody is very happy. We’re excited,” Femi said. “I’m in Los Angeles right now, and it’s very hard to really explain — unless you were alive in the 1970s — what my father did, fighting dictatorship in Nigeria at that time. People were very frightened of the military.”

According to him, the Grammy recognition validates decades of sacrifice, courage and resistance embodied in Fela’s music and political stance at a time when dissent was met with brutal force. He recalled the repeated raids on Fela’s home and commune, Kalakuta Republic, and the severe consequences suffered by his family.

“It was raid after raid. The burning of Kalakuta. His mother being thrown out of the window — she later died from the injuries she sustained,” Femi recounted. “It is so hard to explain to people today how frightening it was for his children at that time. We never knew when he would be arrested, or when he would be released. It was arrest after arrest.”

Fela’s mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a renowned women’s rights activist, died in 1978 after sustaining injuries during a military raid on Kalakuta Republic in 1977, following the release of Zombie, a song that sharply criticised military authoritarianism. The attack marked one of the darkest chapters in Nigeria’s cultural and political history.

Femi stressed that Fela’s music cannot be separated from Nigeria’s political evolution, noting that Afrobeat was deliberately developed as a tool of resistance and social commentary.

“You have to understand how he developed his music over the years,” he said. “From the 1960s — I remember his first hit — then Lady, Shakara. Then he went political. He confronted regime after regime, and then the burning of the house. So yes, Fela had a life.”

Over a career spanning more than three decades, Fela released over 50 albums and used his platform to challenge corruption, military brutality and neocolonial influence. His activism made him a constant target of the state, leading to repeated arrests, imprisonment and censorship, yet his influence only grew stronger.

Addressing contemporary political narratives, Femi firmly rejected attempts to associate himself or his family with political figures and governments that his father opposed during his lifetime.

“When people say that somebody like me supported Buhari, that lie irritates me,” he said. “Or when people say I campaigned for Tinubu — those things hurt me as a person. As Fela’s son, it is impossible for us to be part of any government that is not for the people, especially governments he opposed — people who beat him, arrested him or jailed him.”

He said such claims distort Fela’s legacy and undermine the principles for which the Afrobeat pioneer stood. According to him, the Kuti family has remained consistent in preserving Fela’s ideological position of holding power accountable.

Femi noted that the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award reflects years of dedication by the Kuti family and the global Afrobeat community to sustain Fela’s legacy and keep his message alive across generations.

“My elder sister, my brother Seun, my son Made, the rest of the family — we have all done our little bit to keep talking about him,” he said. “You have musicians playing his music. You have people studying his music. You have Afrobeat artists today inspired by him. People are sampling his music.”

He added that the recognition goes beyond the family and belongs to a global audience that continues to draw strength from Fela’s voice and ideals.

“To top it with one of the biggest awards in the world — the Grammys — what more can we want? But it’s not for the family alone. Fela was a father to many people. That’s why we say ‘our father’. He was a voice for the voiceless in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Reflecting on Nigeria’s development challenges, Femi lamented that many of the issues his father protested decades ago remain unresolved, describing the situation as a painful indictment of leadership failure.

“Africa — Nigeria — should be the envy of the world,” he said. “Our leaders travel abroad, they see how electricity works, how railways work. Their children attend the best universities, but they cannot bring the same template home.”

He described Nigeria’s continued struggle with basic infrastructure as deeply troubling. “It’s shameful that we are still struggling to build roads,” he said. “One kilometre can take years. What is so hard about making Nigeria great?”

On the debate comparing Fela’s legacy with that of contemporary Afrobeats stars, Femi dismissed the argument as unnecessary and divisive, stressing that Fela occupies a unique historical and cultural space.

“Fela is our father,” he said. “He should be placed in a sector of his own. We idolise him and respect him. Wizkid is like a son to me, Seun is my brother. That comparison should never have arisen.”

He urged Nigerians, particularly young people, to focus on addressing the country’s pressing challenges rather than engaging in unproductive cultural rivalries.

“We should be happy that Nigeria is being recognised at the Grammys,” he said. “It’s good for Africa, good for the country. But tribalism, terrorism — those are the issues we should be focused on.”

Femi warned that the burden of change now rests with the younger generation, cautioning that continued apathy could deepen Nigeria’s crisis.

“If young people don’t take the baton and demand good governance, we are going to be in serious trouble,” he said. “Fela spoke, he’s gone. It’s 29 years now, and we’re still talking about the same problems.”

Concluding with a sobering reflection on his own career, Femi said his music remains deeply political because the conditions that inspired his father’s activism persist.

“I’ve been in music for over 40 years, and 90 per cent of my songs are political,” he said. “How long will we keep talking about corruption, kidnapping and poverty? When will Nigeria finally come together to build a nation?”