Seventy-five years after colonial police opened fire on protesting coal miners in Enugu, killing 21 unarmed workers, a landmark judgment of the Enugu State High Court has been formally transmitted to the United Kingdom for execution. The ruling, which awards a total of £420 million in compensation to the victims’ families, marks one of the most significant judicial pronouncements on colonial-era atrocities in Nigeria.

Delivered on February 5, 2026, by Justice Anthony Onovo, the judgment orders the UK government to pay £20 million to each of the affected families. The court also directed British authorities to issue a formal apology and publish it in four Nigerian newspapers and three publications in the United Kingdom.

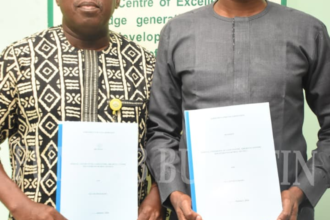

Professor Yemi Akinseye-George, SAN, who led the legal team representing the families, confirmed in Abuja that the judgment has been officially served on the UK government through the British High Commissioner in Nigeria.

“The judgment is now in the possession of the British government for compliance as ordered by the Nigerian court,” Akinseye-George said.

According to the court’s order, the UK is required to pay the full £420 million within 60 days and file a report of compliance within 90 days. Should the British government fail to meet the deadline, the judgment stipulates that a post-judgment interest rate of 10 percent per annum will accrue on the outstanding amount until full payment is made.

The decision stems from the events of November 18, 1949, when coal miners in Enugu, then part of colonial Nigeria, embarked on a protest over poor working conditions, discriminatory labor practices, and inadequate wages. The demonstration, described by the court as lawful and peaceful, was met with gunfire from colonial police officers, resulting in the deaths of 21 miners.

The massacre has long been remembered as a defining moment in Nigeria’s anti-colonial struggle, galvanizing nationalist movements and intensifying calls for independence. However, despite its historical significance, the families of the victims had never received compensation or a formal apology from the British government—until now.

In his remarks following the transmission of the judgment, Professor Akinseye-George described the ruling as a historic affirmation of human dignity and a long-overdue acknowledgment of injustice.

“For seven and a half decades, the families have carried the pain and trauma of that tragic day without redress,” he said. “This judgment represents not only financial compensation but also moral vindication.”

The legal action was initiated by human rights activist Mazi Greg Nwanchukwu Onoh, whom Akinseye-George praised for his persistence in seeking accountability for the colonial-era killings. According to the legal team, the case required painstaking archival research, historical documentation, and extensive legal argumentation to establish liability across generations and international boundaries.

The court found that the colonial authorities, acting as agents of the British Crown, bore responsibility for the fatal shootings. In its reasoning, the court held that the actions of the police constituted a gross violation of the miners’ fundamental rights, even under the legal framework of the time.

Justice Onovo’s judgment emphasized that the passage of time does not extinguish liability for grave human rights violations. The court ruled that the massacre amounted to an unlawful use of force against unarmed civilians and that the victims’ families retained the right to seek redress despite the decades that had elapsed.

In addition to monetary compensation, the directive requiring a formal apology underscores the symbolic weight of the ruling. The court ordered that the apology be published prominently in both Nigerian and British media outlets, reflecting the transnational dimensions of the case and its historical context.

Legal analysts say the judgment may set a precedent for other claims relating to colonial-era abuses, both within Nigeria and across former British territories. The enforceability of the ruling in the UK, however, may involve complex diplomatic and legal processes, particularly concerning sovereign immunity and the recognition of foreign judgments.

Nonetheless, Professor Akinseye-George expressed confidence that the British government would comply with the order.

“This is not merely a legal obligation but a moral one,” he said. “We believe the United Kingdom, as a nation that upholds the rule of law, will respect the decision of the Nigerian court.”

The list of victims whose families stand to benefit from the compensation includes Sunday Anyasodo, Ono Oha, Andrew Obiekwe Okonkwo, Augustine Chiwefalu, Onoh Obiekwe, Livinus Ugwu, Ngwu Ofor, Ndunguba Eze, Okafor Agu, Livinus Ofor, Jonathan Ukachunwa, Jonathan Agu Ozani, Moses Ikebu, Okoloha Chukwu Ugwu, Thomas Chukwu, Simon Nwanchukwu, Agu Alo, Ogbonnia Ani Chima, Nnaji Nwanchukwu, William Nwaku, James Ono Ekeowa, Felix Ekeowa, Felix Nnaji, and Ani Nwaekwo.

For many descendants, the ruling represents a measure of closure after decades of silence and unresolved grief. Community leaders in Enugu have described the judgment as a watershed moment in the ongoing reckoning with Nigeria’s colonial past.

Historians note that the 1949 Enugu coal miners’ protest played a critical role in accelerating nationalist sentiment across the country. The shootings triggered widespread outrage, labor unrest, and political mobilization, contributing to the momentum that ultimately culminated in Nigeria’s independence in 1960.

Yet for the families of the slain miners, independence did not bring justice for their loved ones. The absence of compensation or official acknowledgment had remained a painful gap in the nation’s historical narrative.

By awarding substantial damages and mandating a public apology, the Enugu State High Court has sought to bridge that gap. The ruling signals a broader judicial willingness to confront historical injustices and to affirm that state actors—past or present—can be held accountable for violations of fundamental rights.

As the 60-day compliance window begins, attention now turns to the UK government’s response. Whether the judgment will be contested, negotiated, or honored in full remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that the Enugu ruling has reopened global conversations about colonial responsibility, reparations, and the enduring impact of historical violence.

For the families of the 1949 coal miners, the court’s decision stands as a powerful acknowledgment that their loss has not been forgotten—and that justice, even when delayed by decades, remains possible.